Power. Systems. Change.

Changing a system is easy. Doing it intentionally, not so much.

Ecological examples abound:

The destruction and restoration of the wetlands ecosystem in Santa Ana Pueblo, New Mexico—the location of this week’s annual conference of the Sustainable Agriculture & Food Systems Funders (SAFSF).

The revitalization of the Loess Plateau in China—where, with John D. Liu’s incredible video footage, we produced Hope in a Changing Climate.

The destruction of the Aral Sea in Karakalpakstan (in what was Soviet Central Asia).

Changing systems changes power—and those who have it generally don’t give it up readily. Because everyone who eats is part of the food and agricultural eco/social/economic/political system, change in this system cascades way beyond what we eat and how we grow it—and is totally intertwined with health, energy, climate, and water.

Most systems actually deliver what their creators intended, which may or may not be what the users of the system want or need. There are unintended consequences, but just as history is written by those who win rather than lose wars, so too creators hold the upper hand—whether we describe it as market power, the installed base, or choke points.

But change and stability are interconnected in complex ways. Looking backward, the Greek word and mathematical symbol for change is the Delta (Δ). In geometry and engineering, that same shape, a triangle, is the sturdiest of structures. That’s ironic. That which can withstand change also represents change itself? Perhaps that’s the paradox of leadership—being both the catalyst for change and the guarantor of stability. Change without direction and purpose devolves quickly into chaos.

Change, of course, does not come like a meteor from outer space. Change does, however, often come from the edges of existing systems, from people and institutions just barely within the current system and also from people on the other side of the edge—people excluded or marginalized by a dominant set of interwoven systems. Innovation also drives change and can come both from within and outside dominant systems.

If changing a system is the intent, we should take note of the four fundamental elements of most systems, and understand the differences among the four, as well as the linkages between them.

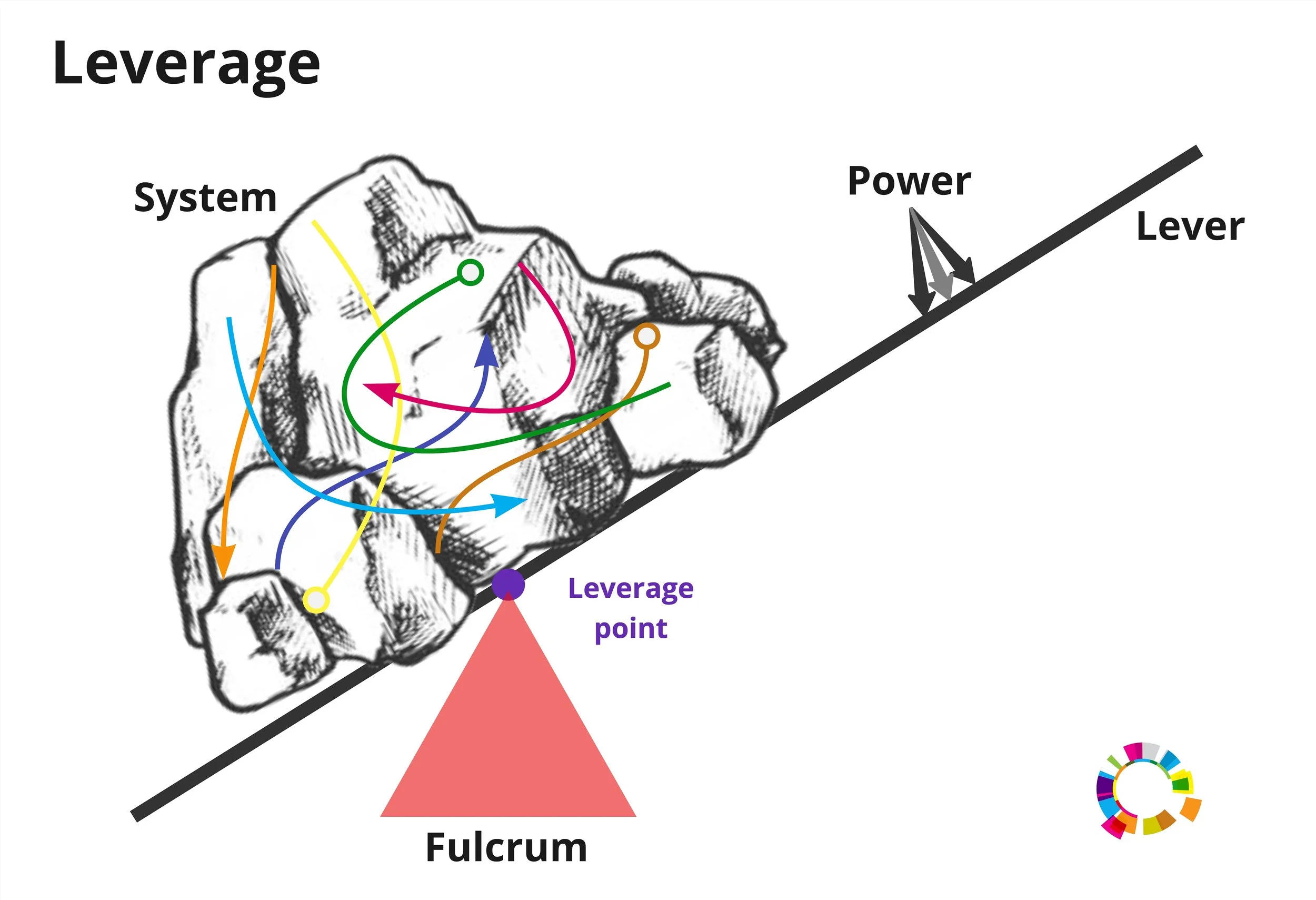

Systems have leverage points, and correctly identifying that critical point, or points, is essential.

Positioning a fulcrum at that leverage point reduces the level of effort needed to move the system.

Once known, the interplay of these two system elements helps identify the kind of lever needed.

The amount of power or energy required to leverage change becomes unmistakably clear.

While simplified, the graphic below captures the relationship of these key elements.

There is, of course, no one leverage point in the sprawling system of food and agriculture in the United States. It is, in fact, not one but a multitude of intertwined systems—and there is no swapping in a new system to replace the current system. Changing it, yes. Transforming it, yes. Shifting the embedded values that define the shape and operations of the system, absolutely.

Stability, an inherent feature of the triangle, is not necessarily in opposition to change—and sustainability brings together aspects of both change and stability. The simplest definition of sustainability is to take only what you need and leave the rest. Applied, that principle would drive massive changes today—while ensuring future generations can enjoy a stable existence.

Whether a wetlands, a plateau, or a sea; a social network; an extended supply chain; policies that shape markets; the complex personal, psychological, and emotional dynamics of family systems; or the systems of politics and government that may seem immutable—all systems can be changed.

The direction of that change, however, is not preordained. Systems that people have designed can indeed be changed by people.